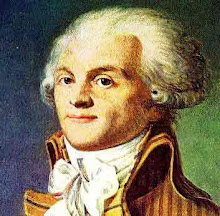

This afternoon Roggespierre received a note from Saint Just, who argued that our earlier post, Extreme Makeover: IndyCar TEAM Edition, contains a fundamental flaw.

You might recall we suggested that because some drivers are worth more than others to those who buy tickets and watch on TV, IndyCar TEAM appearance money should be reallocated to account for driver popularity.

Saint-Just counters that IndyCar team owners don't want compensation based on driver value, performance value, or any other criteria other than that of showing up and putting a car on the track. The owners, Saint-Just argues, see TEAM payments as their money, and they're not interested in sharing it. Team owners apparently fear that, if driver value were used to calculate TEAM compensation, then drivers could argue that they should get a cut.

Fans do not think about such things. Rest assured, participants certainly do.

All due respect to Saint-Just, Roggespierre rejects the notion that this concern exposes a flaw in his proposed Extreme TEAM Makeover. The problem, it would appear, is that the Indy Racing League is afraid of its team owners. Fear might even be justifiable, but the scenario is hardly unusual. For example, suppliers of lithium ion batteries currently wield tremendous bargaining power over their customers. But can we say the same about IndyCar teams?

WARNING: The following is a partial analysis of the IRL's strategic position. It is likely to be dry, and to many, boring. Citizens seeking entertaining IndyCar content this evening should consult other sources. Roggespierre recommends Pressdog.com and MyNameIsIRL.com. Both are excellent. The Indy Idea will return to Revolutionary frivolity tomorrow.

With that, we commence with our analysis.

In his 1979 classic essay, Competitive Strategy, Harvard Business School professor Michael Porter identified what he called Five Forces that determine a firm's profitability. One of those forces is the bargaining power of suppliers. IndyCar team owners collectively supply the entries that compete in IRL races. They are therefore suppliers to the IndyCar Series.

Porter wrote that suppliers can exercise power over a firm. If Saint-Just is correct - and we have every reason to think that he is - then we can assume that IRL managers believe that the team owners hold a measure of power over the series. If true, then Porter would suggest that the teams might quit the series or charge higher prices - appearance fees and bonuses - in exchange for the services they furnish.

Previously, we asked whether or not IndyCar teams do in fact have this presumed power. Adopting the Porter model, they do if:

- the teams' cost of switching to another series is relatively low

- the inputs (to the IRL product) of each individual team are highly differentiated

- the threat of substitute inputs (new teams) into the IRL ranks is low

- the ratio of racing series to teams is high

- the threat of forward integration by the teams is high

- the threat of backward integration by the IRL and its customers is low

- the cost of inputs furnished by teams to the IRL is high relative to the selling price the IRL gets from its customers

Nevertheless, we press on.

"Yes" indicates sources of bargaining power for the teams.

"No" indicates sources of bargaining power for the IRL.

- Q: Are teams' cost of switching to another series relatively low? A: No. Some teams are already in other series, primarily NASCAR Cup, where the cost of additional entries is prohibitive. Any team that switches to a different series will incur a capital outlay for new equipment. Unless a sponsor or an auto manufacturer covers that cost - an unlikely scenario now that firms of all types are reducing costs in series ranging from F1, to Cup, to ALMS - switching is not a plausible option for most IRL teams.

- Q: Are the inputs that each individual team contributes to the IRL product highly differentiated? A: No. The teams furnish commodities - race entries - that are differentiated only to the extent that some drivers are more appealing than others to those who buy tickets and watch on TV. Scuderia Ferrari is the exception, but that is Formula 1's problem.

- Q: Is the threat of substitute inputs (new teams) relatively low? A: Yes. IndyCar equipment is cost prohibitive for prospective team owners unless they have sponsors lined up to underwrite the project.

- Q: Is the ratio of comparable series to teams relatively high? A: No. There are four comparable spectator-supported series - Formula 1, Cup, Grand National, and IndyCar. F1 does not race in the United States and is extremely cost prohibitive. Cup teams have been consolidating for years, primarily to reduce costs via scale economies. That leaves Grand National and IndyCar. The former is dominated by Cup teams and their satellites, making the cost of entry greater than it might otherwise be.

- Q: Is the threat of forward integration by the teams high? A: No. This was already tried. It was called CART. The teams forward integrated, forming their own series, but they didn't go all the way. Rather, they continued to leverage the value of participating in the Indianapolis 500, their largest event and one they did not control. When Tony George created the IRL, the teams' experiment in forward integration reached a crossroads: they could either abandon the strategy altogether or continue on without Indianapolis. Although they chose the latter, the teams transferred much of the financial risk to shareholders via an initial public offering of stock, by definition an exit strategy. The present economic climate, the financial condition of most teams, and the existence of the IRL under IMS control render a new adventure into forward integration a non-starter.

- Q: Is the threat of backward integration by the IRL and its customers low? A: No. In fact, it's already happening. Vision Racing, co-owned by an IMS board member, is an example of backward integration. If another IMS board member were to start her own team, then the existing IRL teams would lose additional bargaining power. The same would be true if, say, Texas Motor Speedway started its own IRL team.

- Q: Is the cost of inputs that teams contribute to the IRL high relative to the selling price the IRL gets from its customers? A: Yes. Herein lies the primary source of bargaining power for the present IRL teams. The supply and demand curves intersect at the point of transaction, the one at which all prospective team owners who possess both the resources and the inclination to present an entry for IRL competition are already doing so. There are only two ways to shift this point of intersection: 1) reduce the cost of entry, or 2) increase the willingness of the able and/or increase the resources of the willing. This is why the next IndyCar spec is so important. It must be inexpensive enough to attract additional team owners that do not have substantial corporate backing. This would not only increase bumping at Indianapolis and car counts at all IRL races, but also reduce the bargaining power of the individual team owners.

In conclusion, the present circumstances provide a rare opportunity for the IRL to impose long-term, strategic policies that will ultimately benefit all of its stakeholders. The teams might resist some imperatives, but they lack alternatives that would empower them to demand the short-term outcomes they desire.

The opportunity to arrange the playing field for the next generation of IndyCar racing is, therefore, at hand. Sadly, it seems that there is no one at the IRL who is in position to take appropriate action.

Roggespierre

I like this, big "R." I saw an interview with Mike Hull on Vs recently, basically talking about a lack of innovation in the series. Reading between the lines, he seemed to be saying, "The great IRL experiment obviously failed, and we're going to fix that now." Scary, reflecting on the management of CART and what that achieved. It occurred to me that we were back to the teams dictating to the series again. And why is that? Because they are perceived to have the power to determine the success, or lack thereof, of the sport.

ReplyDeleteYes, Anonymous, it is frightening. My conversations with those who have been involved in the IRL since the beginning (they are few) lead me to believe that the "old" IRL would have been very well positioned to succeed in the present economy. Unfortunately, that series began to disappear when Toyota (remember them?) was lured from CART. That's when the concessions to suppliers of everything from chassis to engines to racing teams began.

ReplyDeleteThat said, I do have some sympathy given the position the IRL was in back in 2000 and 2001. It had just had its derriere handed to it by CART teams in successive Indy 500s. Its credibility was therefore severely damaged. It's tough to stick to strategy when everybody is talking about how much you suck.