Typically, if you pay $7 for something that is valued in the marketplace at $1.30, then you lose money and look pretty stupid in the process. But what if you could simultaneously sell the same product in another market for $10? Now you've made $3 risk-free and your friends think you're a genius. This is

arbitrage, and it is the emerging strategy to finance the Indy Racing League and its suppliers of racing teams.

For those who are familiar with finance, we note that this is proximate, rather than pure, arbitrage. For everyone else, the technical difference does not matter.

We have established that the value generated by a championship-caliber, one-car IndyCar team over the course of a 17-race season is approximately

$1.3 million. Published reports suggest that the actual price of such an effort is in the range of $7 million to $8 million. So, using these numbers we can assume that the Penske and Ganassi teams incur costs of $7 million per car each year so that they may operate racing teams that are in fact worth $1.3 million. The astute observer will argue - correctly - that Roger Penske and Chip Ganassi do not seem like men who would tolerate losing $5.7 million annually per car.

Team Penske - Abnormal Returns and Market Inefficiency

Roger Penske is not an arbitrageur with regard to his racing operation. Team Penske is financed primarily by sponsorship revenue from the Phillip Morris USA division of Altria Group, maker of Marlboro and other brands of cigarettes. Phillip Morris is subject to severe advertising restrictions enumerated in the Master Settlement Agreement between cigarette manufacturers and states attorneys general.

Unable to advertise anywhere else, Phillip Morris apparently discovered a loophole with Team Penske. The IndyCar Series therefore does not have to compete with more popular media for Phillip Morris's advertising dollars. Its relative value to Phillip Morris USA is significantly greater than it would be for any other sponsor. Penske is thus able to collect, we shall estimate here, $10 million annually per car from Phillip Morris.

Thus, the equation: Penske incurs costs of $7 million for a product that is worth $1.3 million. Then, for all intents and purposes, he sells the same product to Phillip Morris USA for $10 million. Penske can keep $3 million for himself or distribute it to loyal employees (our guess is the latter - he doesn't need the money, and there's a reason employees stay at Team Penske.)

Penske collects abnormal returns because Phillip Morris USA paid him $10 million for a product that costs him $7 million and would be worth $1.3 million to any other firm. This is not arbitrage, but rather a market inefficiency. Advertising via IndyCar racing

truly is worth $10 million to Phillip Morris's Marlboro brand because its paint scheme (we don't say livery here) is iconic, and because its only other alternative is to not advertise at all.

Target Chip Ganassi Racing: Sponsorship by Arbitrage

Chip Ganassi, on the other hand, is fully engaged in arbitrage. Like Penske, he incurs costs of $7 million per car annually in order to operate a racing team that is worth $1.3 million. Chip Ganassi's sponsors do not believe that advertising via IndyCar racing is worth $7 million per car, per season. That is why the bulk of Ganassi's sponsors in fact pay for consideration that not only has nothing to do with consumer demand for IndyCar racing, but also is of far greater value than IndyCar racing in its present form could hope to be. Most of Ganassi's sponsors are, in effect, using his racing team to purchase a product in a different market altogether.

Associate sponsors such as

Tom Tom, Polaroid, Vaseline and Energizer receive concessions from Target Stores in exchange for the money that finances operations at Target Chip Ganassi Racing. Retailers are prevented from receiving kick-backs in exchange for shelf space. The money that goes to Ganassi is more like a kick-aside, but we prefer to call it supply chain leverage. Having incurred costs of $7 million to produce a racing product that is worth $1.3 million, Ganassi then extracts $10 million from the supply chain leveraging activities of Target and its suppliers. Andretti Green Racing has a similar but less lucrative program in place with 7-Eleven, just as Sarah Fisher Racing does with Dollar General Stores. Newman Haas Lanigan leverages Newman's Own products to get funding from McDonald's. Except for Phillip Morris USA and Danica Patrick's backers, IndyCar teams owe virtually all of their financing to supply chain arbitrage.

Notice, however, that arbitrage is strictly a financial engineering activity. No real value has been added to the racing product. No additional fans bought tickets. Television ratings did not increase. In essence, this financial structure eliminates the need for market acceptance of the racing product. Multiply the Ganassi example many times over, and you will begin to understand why CART was unable to land a decent television package despite its armada of high-profile sponsors. That CART was exquisitely financed is undeniably true. That it was something more than a niche sport in the competitive marketplace is not. Many of CART's more lucrative "sponsorships" were generated via supply chain arbitrage. The respective companies signed on for reasons that had nothing to do with consumer demand for CART's racing product.

The Emerging StrategyThis is the path that the IRL is now following. This is the strategy. It won't make IndyCar racing competitive in the marketplace, but that is not the intent. Supply chain arbitrage is the easiest and fastest way for IRL management to generate risk-free returns that will look good to the IMS Board. Supply chain arbitrage will prevent additional heads from rolling across Gasoline Alley. Supply chain arbitrage will pacify teams that are feared by IRL management. Supply chain arbitrage will allow the participants to do the kind of racing they want to do, even if there is virtually

no consumer demand for it.

Supply chain arbitrage is a scourge that could threaten the very existence of the Indianapolis 500 Mile Race.

Supply chain arbitrage robbed the Indy 500 of the

Texaco Star. It felled

Team Valvoline, priced

Hardees' out of Indy car racing, and eliminated the

Budweiser car at Indy. Supply chain arbitrage was and is faux sponsorship that enables team owners to spend beyond the value of the product they produce. The underlying assets happen to be Indy car teams and events, but they could be professional Parchesi and hot dog-eating contests, and it would not matter. It is the derivative - the leveraged supply chain - that counts.

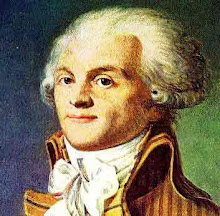

Welcome to IndyCarbitrage**We thought this royal scourge to be dead, but now the serpent is slithering back to the house that Carl Fisher built and Tony Hulman saved. Bonaparte's name is APEX Brasil, a behemoth that exists for one purpose: to extend Brazil's industrial supply chain in the United States. Is there any doubt that Terry Angstadt is now a double-agent, a salesman for both the IRL and APEX Brasil? His racing product has almost no value, but the teams will have his head if he doesn't give them high-tech, high-cost racing. He must construct an artifice, and the best tool in his toolkit is supply chain arbitrage, courtesy of Apex Brasil!

And, by God, it just might work. If you want an IndyCar Series that honors consumer demand, one that creates real value, then you had better hope for a severe devaluation of the dollar (likely, in time) or a flurry of

hostile takeovers.

A devaluation would slay the behemoth APEX Brasil. Takeovers would handle the rest. Why? Because supply chain arbitrage has an Achilles' heel. It is laden with hidden costs! The marketing kids must be in the hospitality tent, drunk and hitting on pole-sitters, when they sign off on these stink bombs! Following hostile takeovers, the pros take charge, evaluate the contracts, and the entire artifice dissolves. Who knew that there is no such thing as a racing team that is paid for by nobody?

If allowed to reach its logical conclusion, supply chain arbitrage will turn the Indy 500 into a bad imitation of the US Grand Prix: half-filled grandstands, a minuscule television audience, drivers known to no one. But the IRL will be profitable. The teams will be sufficiently financed to do the kind of racing they like, consumers be damned.

Louis lost his head, that he be replaced by

Bonaparte.

And, finally, the guillotine blade shall come down, bringing a once undeniably awesome institution to its merciful end.

Show them my head - it's worth it!

Roggespierre - (closing by Georges-Jacques Danton)

**Apologies to Dr. Jack Badofsky